Singer Debbie Harry is 75 next year, and with the launch of her autobiography Face It comes a chance to assess the artistic iconography of the ultimate ‘80s rock chick

From Andy Warhol to H.R. Giger, singer Debbie Harry’s punky look has been co-opted by the art world as iconic of the glossy, perhaps superficial 1980s.

Now nearing 75 years of age and still working as a singer and actress, Harry has produced her first volume of autobiography, Face It, and continues to feature in the neon-lit fantasies of pop artists.

After working as a Playboy bunny, a go-go dancer and a waitress in New York club Max’s Kansas City, Debbie Harry emerged from the sleaze and sweat of the ‘70s punk scene as lead singer of New Wave band, Blondie.

See also: The Arts Society Announces Winner of Isolation Artwork Competition

Through playing at iconic clubs including CBGB, Blondie achieved real success in 1978 with the band’s third album Parallel Lines. Featuring a striking monochromatic cover with photography by Edo Bertoglio, the album boasted pop-tinged hits such as Picture This, Hanging on the Telephone and Heart of Glass.

If the band’s blend of rock, punk, pop and disco caught the attention of the music critics, the public and the art world were entranced by Harry herself, an ethereal yet somehow grounded figure with an angelic face surrounded by a halo of blonde hair, best displayed with massive backlighting and in a short skirt.

Interview

Inevitably this meteoric rise to fame captured the attention of pop artist Andy Warhol, and in 1979, Debbie Harry graced his celebrity-centred magazine Interview on a cover designed and painted by Richard Bernstein from a photograph by Barry McKinley.

Harry made frequent appearances on Warhol’s cable TV shows, once appearing in a head-to-toe Day-Glo camouflage outfit inspired by Warhol’s camouflage paintings, which she insisted he sign while on her body.

Of Warhol, she recalled in an interview with Sotheby’s’ Cheyenne Westphal: “We crossed paths. New York had an active street life—it was a small community back then. You often ran into people. You knew them already or got introduced. I bumped into Andy on Broadway and 13th street and said hello and we chatted about everything. I suppose this is how we met, and our friendship grew from there. I got invited to the Factory and knew others that worked for Andy.

“He was the master of understatement. He’d say ‘Try looking over here’. He was very softly spoken and used a funny Polaroid portrait camera. It was an easy environment and not really a pressured situation. He made it very easy. Andy was part of our legacy and our future.”

In the ‘70s, Warhol was charging clients $25,000 for a portrait, plus an extra $15,000 for every additional panel. He would shoot a portrait subject on Polaroid, print a cleaned-up image onto canvas and deliver multiple screenprints of the work, hoping the client would buy every one.

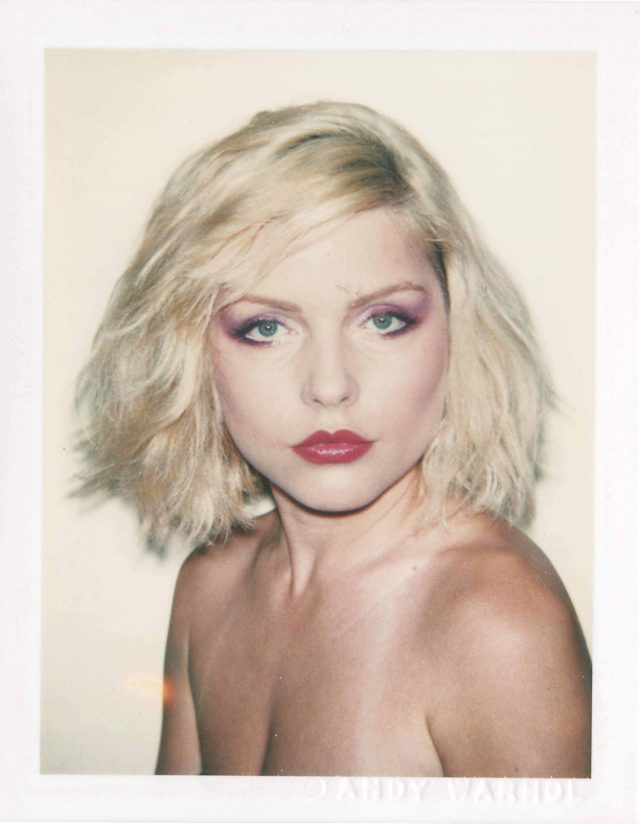

Polaroid

Debbie Harry recalls Warhol’s distinctive Polaroid camera, a Big Shot, which though difficult to focus produced flattering portrait photographs. “To focus you had to move closer or back off,” she remembers. “You really had to have a great eye. It shows you what a genius he was to use this silly camera for these incredible portraits.”

She didn’t respond well to the offer of a bulk purchase. “There were four and it was hard to choose,” she remembers. “They didn’t even try and offer me a discount. They knew I didn’t have that kind of money!”

Warhol also photographed Harry in black-and-white, and ‘painted’ her using an early graphics computer, the Commodore Amiga.

Selected as the cover image for the major survey of Warhol’s portraiture published by Phaidon in 2005, Debbie Harry, from 1980 (our cover image this issue), is one of Warhol’s most accomplished portraits of celebrity. One of only four such portraits of the Blondie star in this rare, 42-inch format, two of which are in the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, this pink version has become one of the best recognised images in Warhol’s oeuvre and the definitive portrait of the 1980s style icon.

Built up of no fewer than five silkscreened layers of ink over the coloured acrylic ground, Debbie Harry sits squarely in the lineage of great portraiture that links the artist’s images of the stellar trinity of Liz Taylor, Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy in the 1960s with his final fright-wig self-portraits in the 1980s.

The originals of Warhol’s Polaroids came up for sale at Christie’s in New York in 2015, realising around $20,000 each, while a Warhol screen print of Debbie Harry reached £3.7m at Sotheby’s in 2011. It’s expected to be included in the major Warhol exhibition at the Tate Modern, London, in 2020.

Backfired

Blondie struggled with problems of personality clashes, bad management, illness and substance abuse, but might have survived if not for the media’s obsession with Debbie Harry. Regarded almost as a modern Marilyn Monroe—vulnerable yet tough, glamorous yet accessible—her image overwhelmed that of the other band members, and when they were famously forced to declare “Blondie is a band”, it was clear their time was up. Blondie split after the sixth album The Hunter in 1982.

Debbie Harry went on to pursue a solo career as singer and actress, encountering another distinctive artist in the form of H. R Giger, the Austrian master of biomechanics and designer of the creatures in Ridley Scott’s movie Alien. Giger’s grotesque Gothic art graced the cover of Harry’s debut solo album KooKoo in 1981—he worked with an airbrush to enhance Harry’s photograph and clothed her in a bodysuit painted head-to-foot in the video for her single Backfired.

Blondie eventually reformed and toured, and Debbie Harry, now aged 74, continues with a solo career. The first 368-page volume of her biography, Face It, is published by HarperCollins in October, featuring a cover photo taken by her bandmate and boyfriend Chris Stein in New York in 1979, overlaid by punk-inspired black and gold hieroglyphics drawn by graffiti artist Jody Morlock.

In many ways a Day-Glo shadow of Marilyn Monroe, connected through Warhol to the glorious past of Hollywood, Debbie Harry’s image remains iconic of the ‘80s, and of an art world fascinated by celebrity, surface appearance and the fleeting nature of fame.

This feature was originally published in the spring edition of Arts and Collections, which you can also read here.

See Also:

Hollywood Icon: Audrey Hepburn and the Photography of Bob Willoughby

Andy Warhol’s Prince Image Ruled Fair Use in Copyright Battle with Photographer