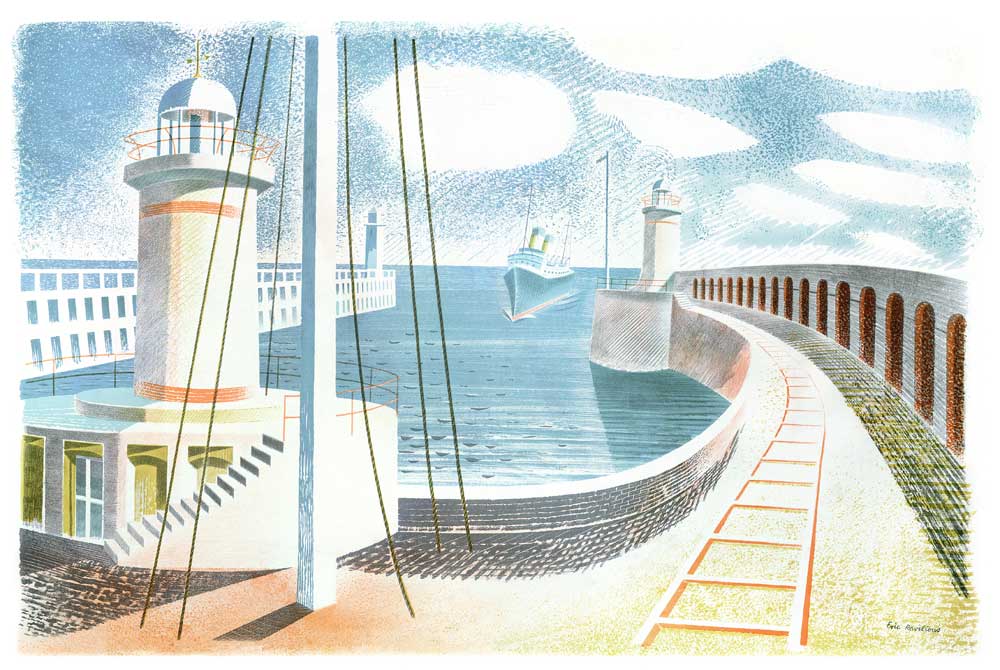

Work by the British artist Eric Ravilious, after 50 years of neglect, is today receiving a new surge of appreciation that is redefining this artist’s significance.

During his short life Eric Ravilious excelled as a painter, watercolourist, official war artist, printmaker, wood engraver, book illustrator, designer of textiles, and a designer of porcelain for Wedgwood and glass for Stuart Crystal. He died in 1942 aged 39 while on assignment as a war artist—from an RAF base in Iceland, the plane he joined on an air-sea rescue mission failed to return.

Struggling for recognition

Ravilious’s many and diverse artistic talents had caused him to struggle for recognition as a serious mainstream artist: his art and those of two friends—Edward Bawden and Paul Nash—did not fit into what was considered the serious art scene of the time which was dominated by the Surrealists, although all three are highly regarded today. As art historian Mary Chamot wrote in 1937, ‘in general, English painters have followed a fairly balanced course, avoiding extremes of abstraction or Surrealism…’

‘Quintessentially English’ are words that are often used when referring to Ravilious’s work. This may even be an aspect that had marginalised his work during his lifetime, branding Ravilious as a talented craftsman, draughtsman and illustrator rather than a mainstream artist. Currently, however, the opposite is true: the English spirit of place in Ravilious’s work and his unique interpretation of what he saw is exactly what make the work so attractive today. Although Ravilious’s work continued to be admired and collected by a small group of devotees in the decades that followed the Second World War, only in the last 10 years or so has Eric Ravilious gained the status he truly deserves.

A developing style

Through his 30s, Ravilious’s style continued to develop. His short period as an official war artist shows a remarkable fusion of his wood-engraver precision coupled with a linear freedom. His friend the artist Thomas Hennell (who was also a casualty of war, 1945) later wrote: ‘Last Friday I was looking at his war drawings, and with increased admiration at the development of his vision and feeling for space and light.’ In his splendid book, Eric Ravilious: Artist & Designer (2013), Alan Powers writes: ‘Ravilious has become more popular in the 21st century than he ever was in his lifetime … Time has shown he has qualities of a different order [compared to some of his contemporaries] and a greater claim to be considered among the significant artists of the time.’

When Eric Ravilious was posted as ‘missing’ in 1942, after the air-sea rescue plane he flew in failed to return to base, Kenneth Clark, Chairman of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee, wrote to the artist’s wife: ‘It is a terrible tragedy for English art: your husband had a unique place as an artist + designer.’

This important tribute aside, here, once again, we find the ‘English’ label applied, and this ‘Englishness’ is a most interesting topic in its own right. What exactly is Englishness? Of the many valuable aspects that makes Alan Powers’ book the most significant to have been published about Ravilious and his art, the concluding essays on ‘The English Question’ and ‘Englishness and Romanticism’ give one of the best insights to have been written on this enigmatic topic.

Key elements

Romanticism is a key element in the ‘English’ mix, although, as Powers points out, Ravilious played an important part in a new trend that introduced elements of hard-edged crispness and a realism that avoids nostalgia. There’s a sense, too, that Ravilious’s work is still very much on the ascent in terms of popularity and collectability. For example, a glance at current ebay listings shows no fewer than 343 of his prints and ceramics, many of which may prove to be bargains, as Ravilious becomes increasingly sought after.

• Eric Ravilious: Artist & Designer by Alan Powers, published by Lund Humphries, 2013, £35.00