An eye for quality and patience are crucial for high net worth individuals looking to start investing in art.

Russian businessman Dmitry Rybolovlev thought he grossly overpaid when he purchased Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi (c.1490) from Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier for $127.5 million in 2013—Bouvier reportedly ‘only’ paid around $75 million for it. However, at one of the most publicised auctions to date, da Vinci’s masterpiece fetched in excess of $450 million at a Christie’s sale a mere five years later.

It’s safe to say Rybolovlev’s investment paid off—and then some. Google searches for ‘investing in art’ hit a record 12-month peak immediately after the historic sale, demonstrating that a new wave of wealthy investors want to take a piece of the action.

The advantage of fine art as an asset is that its value is not affected by the ebb and flow of financial markets. Over the past years, art—especially fine art—has performed better than other investments; analysis of auction house statistics suggests individuals could be getting up to an annual 10 percent return on their investments.

While fine art is an asset that can genuinely appreciate in value, investing in it does have some tangible drawbacks—transaction, ownership and insurance costs can be eye-watering. Authenticity, provenance, tax evasion and looting can also bring substantial worry. This begs the question; can money really be made through fine art investment?

Investing in art: the basics

Understanding the art market is key to making sound investment decisions; this means following auction news, keeping an eye on burgeoning trends and speaking to specialists and curators.

According to Zohar Elhanani, CEO of online art information service, MutualArt, rarity is the foremost factor that can drive the value of art. ‘Original works, such as oil paintings, will tend to fetch a higher price on average than a work produced in editions, such as prints or photographs. The scarcity principle applies across collecting categories as well as other media,’ he adds.

Similarly, ‘The work of a prolific living artist is likely to be viewed as less scarce than that of an Old Master artist with a limited number of authenticated works to their name.’

When asked, anyone with a knowledge of the industry will advise to exclusively buy and invest in pieces that hold meaning. Purchasing works of art for the sake of the name attached to them or their past auction history could prove to be a monumental investment faux-pas. To Elhanani, this is because markets are regularly changing in response to supply and demand. He adds: ‘While the fame—or notoriety—of a particular artist may lend name recognition and a buzz to a particular work, there’s little evidence that consistently connects fame to value.’

There’s no question that certain artists are established names in the industry; for major collectors, owning artwork from one of these ‘blue chip’ creatives is the driving force behind a particular purchase. ‘However, there are as many possible auction outcomes as there are factors that contribute to the valuation of an object—simply owning a work by a famous artist will not guarantee its value,’ Elhanani warns.

While the fame—or notoriety—of a particular artist may lend name recognition and a buzz to a particular work, there’s little evidence that consistently connects fame to value—Zohar Elhanani, CEO, MutualArt

An ‘outrageous’ status

Similarly, an artist’s status as ‘outrageous’ or ‘innovative’ will not do much to increase their work’s worth. ‘The value of a work of art that creates a public sensation can be immensely variable. For example, van Gogh’s vivid post-impressionistic canvases were largely derided in their day and wholly uncommercial, but now an original oil can fetch tens of millions at auction. By contrast, the contemporary artist Damien Hirst—who also pushes the boundaries of his time—held a “white glove” auction dedicated to his work, selling each and every work.’

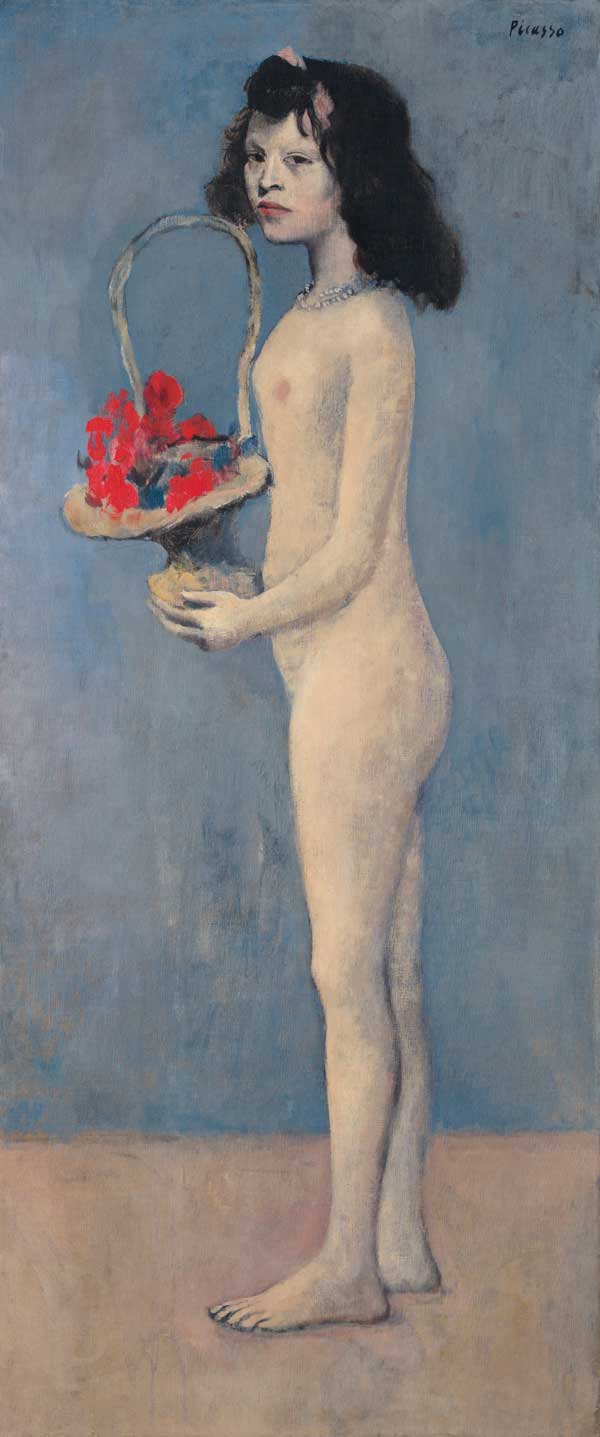

It’s not uncommon for there to be huge variations in price and value of a work of art depending on its subject matter or date completed—doing research is key. Certain pieces by the same artist will be worth a lot more if they’re from a sought-after series or made in a year that has particular relevance to the artist’s work. This is best seen with Picasso paintings completed in 1932—the artist’s annus mirabilis—as well as pieces from his Rose Period, spanning from 1904 to 1906. Fillette à la Corbeille Fleurie (Young Girl with a Flower Basket), which the Spanish artist completed in 1904, fetched a staggering $115 million at a Christie’s New York sale in May 2018.

Fillette à la Corbeille Fleurie, 1905 Oil on canvas

154.8 x 66.1 cm.

Image courtesy Christie’s

Lastly, ensuring the provenance of a work of art is essential before purchase. Elhanani emphasises its importance: ‘Provenance is a critical component in establishing the authenticity of a work of art…having complete sale records allows a potential buyer to have confidence in the title, or absolute ownership of the work.’

On the growing issue of art forgery, MutualArt’s CEO warns investors to be wary when certain provenance documents cannot be supplied or if the information appears incorrect or suspect. ‘Provenance can be more difficult to establish for Old Master works, where the record of ownership is extensive and not always consistently documented across centuries. Many recent artists, such as Gerhard Richter, have strict numbering systems for their work, which helps to ensure fakes or forgeries can be swiftly identified. Other artists’ estates have established foundations that rely on expert knowledge of the artist’s working practice to authenticate works and remove fakes or forgeries from circulating on the market,’ he adds.

Investing in art: improving returns on investment

The best way to enhance ROI? Looking after a work of art, Elhanani says simply. ‘Good condition is paramount. Keeping the work in good condition could be as simple as ensuring a photograph is framed with UV-appropriate glass or protecting a sculpture from damage by keeping it away from high-traffic areas.’

As for fine art, the MutualArt CEO advises a more cautious approach to conservation: ‘In the case of works that use rare or scarce materials, conservation may be best managed with the advice of a professional.’

Condition aside, other factors that can impact the value of a work of art include the provenance or part ownership and the exhibition history of the artwork itself. Exhibiting it, loaning it to a museum or gallery for a defined period of time or having it included in a catalogue raisonné—the official survey of an artist’s work—can all enforce its provenance and, therefore, increase its value. To high net worth individuals with substantial budgets and a love for collecting, Elhanani suggests buying ‘works that are in good physical condition, by artists whose work is widely exhibited and who have an established secondary market and strong representation by a dealer.’

Investing in art: the right time to sell

Investors and collectors alike may struggle to determine the right time to buy or sell a work of art. This decision can be influenced by a wide range of factors, including collection management or a change in personal taste. ‘Collectors should assess the artist’s recent auction activity and exhibition history,’ Elhanani says, ‘Consider which sale avenue, private sale or auction is best suited for their work,’ the CEO adds.

Any work of art contains both an intrinsic, intangible value and a market value—either for the purpose of sales or insurance. Specialists can help potential investors and collectors discern the latter: ‘When a work is consigned to an auction house, specialists in a particular collecting area assess a wide range of factors such as authentication of the work, particularly for older works of art; whether the work is an original or an edition; its physical condition; past prices for the artist’s similar work; and how widely the work has been exhibited and written about,’ Elhanani reveals.

In cases where there is significant public awareness of the artist and interest in their work, an auction house may also generate competition for the work. Beware of fluctuating or depreciating values—investors should seek out artists with strong gallery representation, as this means the artist’s work is being championed at the primary level. On the secondary market, an artwork’s value can fluctuate dramatically.

However, there are also trailblazing models that allow individuals to release capital tied up in their assets without the need to sell their artwork. OMNIA Asset Solutions is one such model. ‘Collectors all share the desire to release capital tied up in their assets, which is notably difficult to do without having to sell,’ says Amelia Hunton, managing director of the company. ‘But this is what we offer. An alternative solution where they don’t have to sell the artwork, instead they pledge the artwork in return for an agreed annual income over a fixed period,’ she adds. This way, collectors are able to generate a cash flow off securitised assets with the additional benefits of the running costs—such as insurance, storage and transportation logistics—being covered by OMNIA.

This feature first appeared in Arts & Collections Volume 3, 2018. Click here to view the digital version of the magazine.

See also: Uncovering the World of Rare Book Investment with Pom Harrington of Peter Harrington London