New York-based Aby Rosen, collector of art pieces by Warhol and Hirst and more, talks about the ebb and flow of his outstanding collection of famous contemporary art, the trends and what inspires him to buy and sell in particular Warhol and Hirst.

In real estate, they say that three things matter: location, location and location. Aby Rosen’s best-known buildings stand across from each other on Manhattan’s Park Avenue—the 1959 Seagram’s Building by Ludwig Mies van de Rohe, and Gordon Bunshaft’s modernist glass box, the Lever House (1952).

Aby Rosen also owns some 80 Warhols, the last time he checked. ‘Perhaps it’s a bit more now,’ he says after a moment’s reflection.

‘About ten to twelve years ago, I started buying Warhols and Joan Mitchell,’ the real estate developer and collector recalls. ‘I think my first major painting was a Joan Mitchell diptych. I was working with an art adviser whose name is Richard Marshall, who’s a friend of mine. I worked with him for a couple of years to get a better understanding of what to buy, which direction, what kind of quality, which year—then I started basically doing my own thing’.

‘A lot of friends of mine were in the art world, and that’s how you start, dabbling by yourself, and getting some advice from others,’ Aby Rosen explains. ‘But I think the only way to do it right is to be free after a while, and do whatever you want to do. Just like a child, you need to learn how to walk, but once you walk, you’ve got to go. You can’t be forever associated with an adviser because then you’re never going to do it.’

Aby Rosen is the first to acknowledge that he might be compared to the child who, once he starts walking, immediately begins running. He’ll also admit that doing what you want to do is easier when you can pay your own way, at Warhol prices. ‘I’ve never seen anybody without the capital generate a really good collection. Money and collecting go hand in hand.”

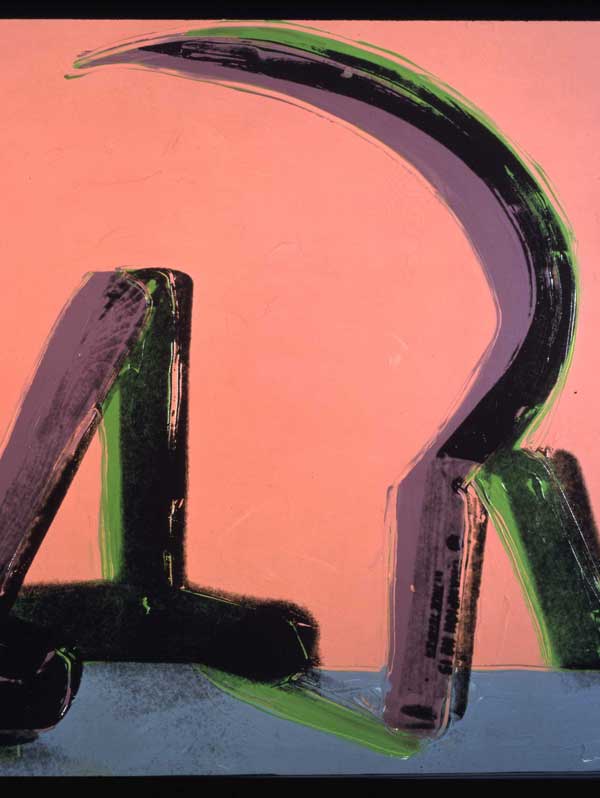

Over the last decade, Aby Rosen’s taste hasn’t changed much. He’s continued buying Warhols, usually participating in auctions where Warhol records are broken. He has also collected works by Jeff Koons, Damian Hirst, and, more recently, Christopher Wool, the painter who includes words on his stark white canvases. Around eight years ago, Rosen began buying the undervalued (and some say under-appreciated) late works by Pablo Picasso. ‘I think it has to do with growth and with knowledge of the market. I think it has to do with understanding the artists better.’

Born in Frankfurt, Germany, to Holocaust survivors (his father was from Poland, his mother from Belgium), Rosen grew up surrounded by eighteenth and nineteenth century paintings that his parents collected. ‘My parents also had heavy baroque paintings with gold on the wall, and that’s not something that I gravitated to,’ he recalls. He studied law at university level, but has never studied art history.

‘I like art that is visible, that is easy to take in. I don’t like the dark colours of this eighteenth and nineteenth century stuff. It’s very dark and very heavy. I like lighter colours and lighter art.’

That approach rules out the work of Anselm Kiefer, the painter and sculptor whose work comments on German history in the twentieth century. ‘I like Kiefer, but it’s too textural, there’s too much going on, too much interpretation. Every time for me, when you have to reach too much into the art, it’s art that I don’t want to own.’

‘Art for me has to be very simple, and self-explanatory. It can be very abstract, it can be very specific, but it has to be easy to understand. If you have to have the artist explain it to you, it doesn’t work for me. It should work, period.’

An artist who does work for Aby Rosen is Damian Hirst—so well that the collector exhibited a colossal bronze Hirst sculpture of a grotesque pregnant woman that rose through several floors of the courtyard of the Lever House, the landmark skyscraper for which Rosen owns a 99-year lease on Park Avenue, just diagonally across from the Seagram’s Building. ‘Damian is “bang”—it’s right there. There’s no hidden message. You don’t have to search for the hidden meaning of this or of that.’

Aby Rosen has a logical explanation for the soaring rise in Warhol’s prices in recent years. It’s partly a result of the flow of capital into the art market, as evidenced by the participation of buyers like himself. But it’s not just money, he says. The collector, who came to the United States some many ago, talks about Warhol the way that other immigrants talk about the Statue of Liberty.

‘They’re in demand because they represent the classic icons of America—the Elvis, the gun, the portraits. They’re about celebrities. We all love celebrities. People don’t admit that, but that’s what Andy Warhol was all about. He took what we all know and put it on a piece of paper.

‘Talk about the Car Crash,’ he says, referring to the Warhol painting Green Car Crash, from the 1963 Death and Disaster Series, which sold for $71.3 million at Christie’s five years ago. It was an auction record for Warhol, although a Marilyn broke another record a few weeks later, selling privately for $80 million to Steven Cohen, another real estate mogul. ‘It’s harsh, but it’s reality. It’s like the Jackies, These are things that we all know. We all know Marilyn. We all know Mao. He took the iconic images and made them accessible to everybody.”

Competition among collectors

Rosen downplays the notion of competition among the major Warhol collectors.

‘There’s so much art out there,’ Aby Rosen says, so that collecting is more collegial than one might imagine. He recalls a moment when a dealer had two Warhols available, and both he and the collector Peter Brant were interested. ‘Peter called me up and said: “Which one do you want?”. He bought a huge oxidation painting, and I bought a huge shadow from the same seller out of Europe.’

Under Aby Rosen’s ownership, the Lever House has introduced a rotating exhibition program. The sculpture Aluminum Foil Thing by Tom Friedman was there a few summers ago. Like Friedman’s other satirical works, it was a construction of seemingly worthless material, a suspended mini-universe of elements of aluminium foil, which seemed to confirm (and mock) the widely held notion in the real estate business that anything you build in Manhattan will have value.

A show of new works by Damian Hirst in collaboration with Gagosian Galleries went on view to coincide with the contemporary auctions in the spring art boom of 2007. (Tom Sachs’s huge white sculpture, Wind-Up Hello Kitty (2007), is there now.) At the Seagram’s Building, the Four Season’s restaurant has had art on view since the space (designed by Philip Johnson) opened in 1959. Rosen envisions more public art on the plaza in front of the modernist Mies van de Rohe structure.

For now, Rosen stops short of trying of establish his own museum. ‘There’s a lot of vanity in doing that. Not that I’m not vain,’ he says. Rosen had included a ‘Kunsthalle’ for contemporary art exhibitions in plans for a skyscraper, designed by Sir Norman Foster, that he proposed to rise above the existing building on 980 Madison Avenue that once housed the Parke-Bernet Galleries. The Landmarks Commission of New York City voted down that idea.

Since then, Aby Rosen has aligned himself with another institution, The New Museum of Contemporary Art, which has its new headquarters designed by the Tokyo firm SANAA Ltd. on the Bowery, in a Manhattan neighbourhood once notorious for its drunks and flophouse hotels. Locating an art museum on the Bowery shows the vitality of New York, says the man who always eyes real estate for its future value. Rosen stresses that all signs from New York point to the city’s continued position as the centre of the art world, despite competition from London.

‘I think New York is still the dominant area. It’s a far broader market,’ he says. ‘There are more galleries here than anywhere else. There’s so much quality of production here. Look at the American artists and look at the American buyers who will buy art.’

Rosen is among them, although he says he can go for months without making a purchase, and then buy five or six works in a week. He says trading up is the only way for art to generate the capital to buy more art: ‘I don’t say I’m in the art business, but a good collector keeps on rotating his art, keeps on selling.

You move up your threshold, and that’s why you need to trade.’ The market bears out this approach. Just last summer, Adam Sender of Exis Capital, another New York player at Aby Rosen’s level in the contemporary art field, noted at the market’s height that he had paid for all the contemporary art that he had bought in the previous few years (Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, etc.) by selling one fourth of the art he owned—an admission that his art, all contemporary, had quadrupled in value then—and are inching back up now.

Aby Rosen’s collection is indeed new, all of twelve years old. Yet, as with real estate, he’s thinking about the future.

‘Collecting art is eventually about giving it to somebody. Giving some to the kids is fine, but eventually you’ve got to do something with it.’

It’s a long way off, but museums on both sides of the Atlantic are already lining up.

Read about: Art Dubai: Craftmanship of Cartier’s Jewellery