Painting had rarely come easily to Henri Matisse, the Fauve. Throughout his career, he questioned, repainted, and re-evaluated his work.

In 1905, Henri Matisse left the dusty heat of Paris to spend the summer at Coullioure; a small fishing village on the southern coast of France. For some time he had felt disillusioned with his painting. Up until then, Matisse had been influenced by the Impressionists, but he began to find their art “a completely objective art, an art of unfeeling”. Determined to find his own more personal approach, Coullioure, and the dazzling sunlight on its boats and harbour, proved a catalyst for one of the most exciting early periods in Matisse’s long career as a painter.

At Coullioure, Matisse was joined by his friend, the painter Andre Derain. They began a series of paintings that caused a sensation when shown at the Salon d’Automne in Paris later that year, in 1905. Abandoning the Impressionsts’ theoretical approach to colour and direct representation, Matisse and Derain’s radical new paintings, more influenced by Van Gogh and Gauguin, were bold and abstract and used expressive brush strokes in pure, vibrant colours.

The paintings of the Fauves (Wild Beasts), as the group of artists which also included Braque, Marquet, Roualt and Vlaminck later became known, shocked and enraged both the public and critics. “A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public,” exclaimed the art critic Mauclair.

Among the first to appreciate Matisse’s ‘wild’ paintings was the formidable Gertrude Stein renowned for her witticisms—“In France, one must adapt oneself to the fragrance of the urinal”—and for her gatherings of artists, writers and critics at her ‘open salons.’ She bought Matisse’s most derided painting in the exhibition, Woman with a Hat (1905). The portrait of Matisse’s wife Amélie, was added to Stein’s collection of controversial works by the most avant-garde artists of the day.

These included paintings by Cézanne, Picasso and Braque, that hung from floor to ceiling at her house on the Left Bank in Paris. Stein’s sister-in-law, Sarah, who attended Matisse’s painting classes in Paris for two years, also became an avid collector purchasing over forty paintings—“Matisse opened new horizons for us and enriched us with his art and friendship,” she recalled.

For Matisse the new-found freedom of expression for his painting was the breakthrough he had been looking for. Through colour and line he could evoke his sensations, rather than representations, of reality, as he explained: “While working I never try to think only feel”. Prior to starting a painting, however, he described the importance of the initial concept for a composition. “For me, all is in the conception. I must therefore have a clear vision of the whole from the beginning.”

Initially Matisse would make drawings directly from the model to understand the form of his subject. Then, to find a way of condensing his sensations further he would often work from memory. Years later in 1954, he recalled his ‘revelation in the post office’ where, thinking of his mother while waiting for a phone call, he absent-mindedly drew a portrait of a woman’s head on a nearby postal form—“I drew without thinking, my pen going by itself”—and found he had drawn with remarkable exactness his mother’s face. “I was struck by the revelations of my pen, and I understood that the mind which is composing should keep a sort of virginity in relation to certain chosen elements and reject what comes to it by reasoning.”

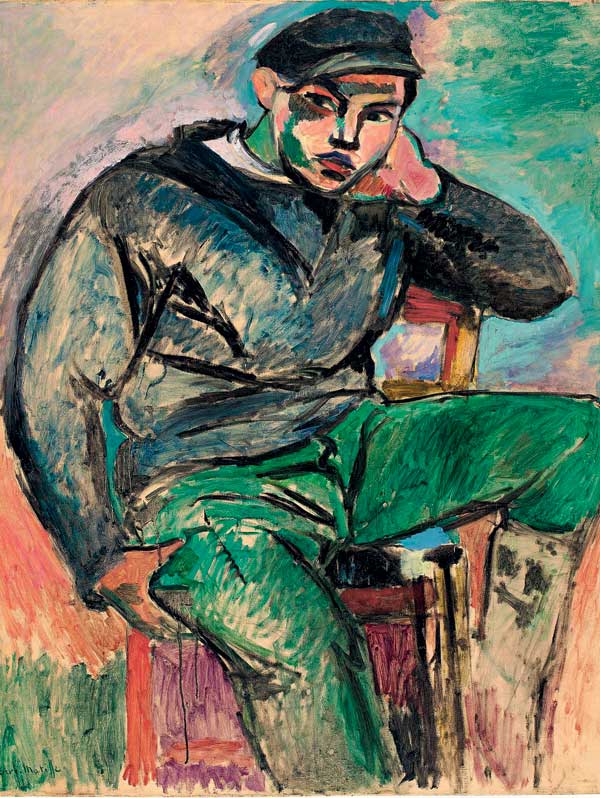

Rather than overworking a single canvas, Matisse frequently painted two or more versions of a particular subject on similar size canvases. “I always use a preliminary canvas the same size for a sketch as for a finished picture and I always begin with colour.” In this way he could to develop the subject further and allow for comparison. It also kept the lightness of touch and spontaneous freshness of the painting that he believed so important. Young Sailor I (1906) and Matisse’s second version of the same portrait clearly shows this process.

See also: THE SUBLIME

Similarly the grouped figures in Luxe, Calme et Volupté painted in 1904, where Matisse has used broken brush strokes of pure colour, was a theme developed three years later using an entirely different technique. Influenced by the figures in Cézanne’s Les Grandes Baigneuses, Matisse selected fewer figures in his later versions: Le Luxe I and Le Luxe II painted from 1907-8. He also simplified and flattened the figures and background in the final version to give maximum impact to large areas of unbroken colour. “My destination is always the same but I work out a different route to get there”—he wrote in his Notes of a Painter in 1908.

Matisse’s Fauve period lasted only two or three years before the next brief, but important, influence of Cubism. Earlier, during the same period as Fauvism, Picasso and Braque had formulated Cubism; an entirely new type of pictorial space which derived from Cézanne. Following Cezanne’s method of using multiple planes and flattened perspective to depict his subjects, Picasso and Braque took this further in their paintings, using multifaceted viewpoints of objects reassembled in abstract form.

Influenced by Cubism, Matisse’s painting took on a new austerity and subdued colour palette, no doubt anticipating the dark beginnings of World War I. In his three versions of interiors with a goldfish bowl made in 1914, Matisse begins with a vertical canvas for his first version.

In this he flattens and tilts the perspective up towards the picture plane while in the second composition, Goldfish and Palette (1914), he abstracts further. The composition is divided dramatically into vertical planes with selected elements of the wrought iron balcony seeming to act as supportive structures to emphasise the centrally placed goldfish bowl. His final version includes a reclining figure.

“What interests me most is neither still life nor landscape but the human figure. It is that which permits me to express my almost religious awe towards life.” Throughout Matisse’s career, though he painted many landscapes and still lifes, it was the figure that remained his most constant theme.

From 1917, Matisse lived in Nice, in the South of France, until his death in 1954. There his transition from paintings of intimate interiors, often containing a single reclining figure, with glimpses of palms and sea beyond, moved on to his last explorations of colour. Matisse’s dramatic and abstract cut-outs were the final masterpieces of one of the twentieth century’s most significant and influential artists.

See also: LUCIAN FREUD THE GREAT BRITISH ARTIST